In the fourth in our series of pieces to mark the opening for entries of this year’s Bruntwood Prize, Stewart Pringle discusses magic boxes and the transporting power of theatre.

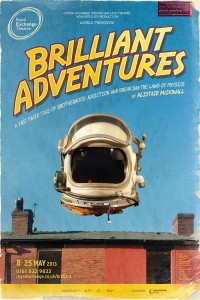

There’s a cardboard box in the run down council flat setting of Alistair McDowall’s Brilliant Adventures that is (spoiler alert) a time machine. It’s not a metaphorical time machine. It actually is a time machine. You can use it to travel in time. Real people use it, in their real lives, and that one, simple, brilliant conceit both warps reality around it and makes a human story of brotherhood and loyalty pop into a new and vivid life.

When a writer, or a theatre maker, does something like that, it makes me feel a little giddy. A little like punching the air. It has an audacity to it and a refusal to countenance boundaries, boundaries between high and low art, sense and nonsense, between different levels and depths of fiction. It has an ambition that practically glows.

For me, theatre is a medium of transport and transformation. At its best it’s a ticket to another world or another way of thinking. I want to see theatre that finds the sweet spot between the greatest poem ever written and Nemesis at Alton Towers. That can rhyme ear-splitting explosions with the most intimate gestures. That makes you want to invent a special little dance, just for it, and dance it right out of the venue and half way down the street. There’s no schematic for it. There’s no minimum or maximum scale. It can be done with millions of pounds of set dressing in a massive warehouse or by a single person speaking brave new truths or beautiful new lies in a dark room.

Some theatre kindles, some works catch fire, and it’s all you can do to carry that flame on. Theatre that defies rules and redefines the possible. Theatre that is braver, softer, more angry, patient, gentle or violent than the world outside of it. Theatre that maps the plate tectonics of the future, that opens up into unknown territories where people and language are radically altered but absolutely familiar.

And I write about it because I’m worried that you’ll miss it. I’m writing about it so I don’t have to come round to your house and physically drag you to the theatre. Nobody needs that. I’m the guy on the street corner with the placard and the megaphone. The end (of the run) is nigh! Get your fucking skates on!

Not all theatre makes me feel that way. Most of it doesn’t, in fact, and it’s important to write about that too. I don’t want you going to hell any more than that dude on the street corner does.

Writing in what I guess is a sort of critical community makes you aware that not everyone has the same idea of hell, or the same idea of magic. But there’s nothing quite like those moments when you see the signal spring up in all the distant watchtowers, the news that in a dark room somewhere someone is doing something remarkable. And they’ll take you with them, and into them, but they won’t be there forever.

Until the mid-1990’s there was a theatre in Keswick called the Blue Box theatre, one of the country’s smallest, a few cabins of bright blue painted wood. When I was a kid I used to think it was the TARDIS, and though I never actually went inside it, now that I spend a lot of time in theatres I think that’s what I always want them to be. A magical box where someone brilliant, or some brilliant people, reach out their hand and take you on an adventure.