In the first in a series of pieces to mark the opening for entries of this year’s Bruntwood Prize, Andrew Haydon discusses the theatre that makes him want to write about theatre and the evolving nature of The Job.

No one starts off wanting to be a theatre critic, I don’t imagine. I definitely didn’t. I guess when I went to university I nursed a vague ambition to be a literary critic/Eng.Lit. lecturer, mostly because it seemed like a pretty amenable lifestyle (read a lot of books, take a few seminars, wear tweed).

Then, in my first year at Leeds I got completely blindsided by the National Student Drama Festival. I’d never really had any particular interest in, or appreciation of, theatre before then. I’d been to most of the student productions at Leeds since I’d been there, but mostly to save me reading the plays (Berkoff’s Decadence, Beckett’s Endgame, a bunch of Pinters). But my hoursemate-to-be was in a show that had been selected, my Granddad lived in Scarborough, and it just seemed like a fun thing to do for a week in the Easter holidays.

The NSDF ran (and indeed still runs) a festival magazine, Noises Off, which printed daily reviews, comment pieces, cartoons, and so on. Back in ‘97 it was an all-night operation run on high caffeine levels and indoor smoking. It was about the closest thing to heaven I had ever encountered. The first year there, I didn’t write a single thing (Maddy Costa won the student critic prize). I went back the next year and wrote quite a bit. All of it excruciatingly bad. I went back the year after and wrote slightly better reviews (and Duška Radosavljević won the student critic prize). I went back the year after and wrote almost passably and intelligently. Then that year in Edinburgh, the new website CultureWars wanted someone to review plays for them in return for free tickets to those shows. This was the best thing I’d ever heard of, so I did that. And carried on, sporadically for them back in London. And, without ever particularly intending to turn it into a career, it gradually became what I did, up to the point where I started getting paid by people – Time Out, the Financial Times, the Guardian – to write stuff for them, alongside my still-unpaid blogging. And, over the course of those years, starting with a base of practically zero knowledge of theatre, I also read up on everything, learned the history of recent theatre, while living through another decade, nearly two decades, of developments.

[As an aside: it is also interesting for me now, to look back to things I wrote in ‘01, ‘02, or ‘03 and be both amazed at how utterly dreadful and callow I was in my pronouncements and, at the same time, how recognisable my embryonic tastes and preferences were, even then.]

In a weird way, since 1997, I don’t think “what theatre makes me want to write about theatre” once occurred to me as a question. In a way, that never felt like “The Job”. But I think The Job has changed, or at least I’ve changed my approach to it. When I started out, mentored by seasoned pros like Ian Shuttleworth of the FT and Robert Hewison of the Sunday Times, The Job was a matter of journalism. We covered theatre, we reported on theatre. We tried to give a sense of what a particular production was like – pretty much every night of the week. Theatre itself was what drove us to report on theatre: just generally giving a damn about the state of the artform. I’ve never asked, but I suspect that’s how a lot of critics see their job: as kind of particularly well-informed weathervanes, telling everyone which way the winds are blowing from a particularly privileged vantage point. Obviously personal taste and political preferences come into that. The narrative that the Guardian’sMichael Billington often describes, for example (personal/political New Writing fighting a brave rearguard action against the ravages of Philistine devising), clashes entirely with the growing story that Quentin Letts’s of the Daily Mail tells in each successive review about public money being used to fund ever more debauched scenes of depravity at the behest of a shadowy Liberal Elite to further their ends through politically correct brainwashing.

So, I suppose, as well as wanting to just do the best job you can of reporting what a play *is like*, you also find yourself constructing a wider narrative about the “progress” of this beloved artform. And, it’s not impossible to find yourself seeing some examples of theatre that you consider to be its apexes (so far, in your experience). Oddly, my relationship with such apexes is quite a difficult one, at least as a critic. At a very basic level, this is partly because it’s much easier to write about something that you find deplorable than something by which you’ve been blown away.

Furthermore, perhaps because of what I find brilliant – often elusive, ineffable, inexplicable work – it often feels that the work itself is resistant to traditional modes of critical writing. The best work almost forces you to invent a new vocabulary, which is, as you can imagine, bloody hard work. But, at the same time, it is this work that you live for, as a critic. Hell, it’s what you live for as any sort of theatregoer: that night where theatre does something to you, or shows you something, or makes you think something, that you’d never even imagined before.

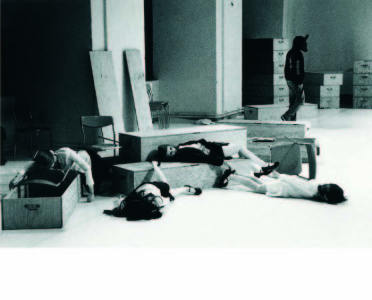

What is that work? Well, I could give recent or historical personal examples, from Katie Mitchell’s 1997 NT production of Attempts on Her Life through to Ali McDowall’s Pomona, Chris Goode’s Men in the Cities or Ivo Van Hove’s Young Vic A View From the Bridge via Gisele Vienne’s I Apologize and Sebastian Nübling’s Three Kingdoms (all of which I think I entirely failed to do justice to in my write-ups, by the way).

At the same time, work which seems perversely determined to smash up everything I hold dear about theatre makes me want to write about it. Angrily, usually. Or at least sadly, reasonably, but implacably.

I guess, like anything, theatre is a small, never-ending culture-war. A series of attacks and counter-attacks by artists against each other, all trying to explain the violence and horror, beauty and brilliance of the world to their audiences. In this, the critic is a war correspondent who cannot help but take sides. On a good day, the compulsion to keep on going back is probably as much to do with urgency and adrenaline as anything. And you never know if it’s going to be a good day until you’ve seen the show…

Related Material

Interview with Alistair McDowall on Pomona

Simon Stephens & Sean Holmes discuss Three Kingdoms