Meet the Shortlist- Tim X Atack

This year the Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting Judges decided upon a winner anonymously on Monday 23rd October. The winner and Judges Awards will be announced…

The Royal Exchange Theatre, the home of the Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting, may be closed, our stages may be quiet, our hearts may be breaking, but we continue to be creative, to be writers, directors, artists and theatre makers. We are in unknown territory and are busily making plans about what this means for our future work. We do not yet know what the impact will be across our sector, for the artists who we make work with, the participants that we support and for our audiences going forward.

We are exploring ways in which we can all remain connected and optimistic. Human connection is something we all need, to share stories, to engage our imaginations and emotions. As well as reposting our writing Toolkit– winning writers have been offering insight and (hopefully) support from lockdown.

Tim X Atack won the Bruntwood Prize in 2017 for his brilliant play HEARTWORM

Monday 23rd of March

The radio isn’t on, the TV has no antenna.

I’ve been going online for info a couple of times each day, perhaps just before lunch, then at about 6pm. The weird music of every headline containing the same word. Coronavirus: the second-largest crisis currently facing humanity.

Sure I want to behave responsibly, to be properly informed, and of course it’s fascinating to watch expertise-dodging governments getting slapped in the face by the world’s most immediate FACT, daily. But it would also be all too easy to get constantly sucked in to the news cycle.

So first a chat with my partner Tanuja over breakfast. I stayed up late last night finishing a novel (Fingersmith, Sarah Waters) that T read four years ago and has been waiting all that time for me to catch up, so we can talk about it. I tackle novels at snail’s pace. Non-fiction? Zip through it.

We talk about plans for the day. She sends me a link to an article by Mac Wellman, The Theatre Of Good Intentions, first shared with her by playwright Dipika Guha.

It’s a witty and angry polemic against the unthinking conventions of American theatre, from 1984. Even though it’s hyper-male, full of a sense of unearned authority (and there’s much I disagree with) I love it. A lot of his argument still feels current.

A nice electric feeling first thing in the morning – I’d recommend it, as well as the article it makes me re-read straight after: Elinor Fuch’s EF’s Visit To A Small Planet, that I first encountered thanks to Vinay Patel. It’s about how we think when we criticise theatre … and IMHO has great relevance to how we write it and make it, too.

Texts from my mother up in Yorkshire, living alone, in her 70s. She’s just received half a home delivery from Sainsbury’s. “My whisky bottle came in three little bottles, so that’s alright.” Getting her priorities straight as ever.

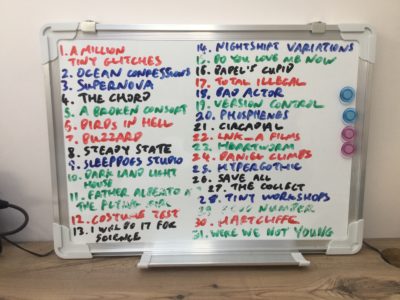

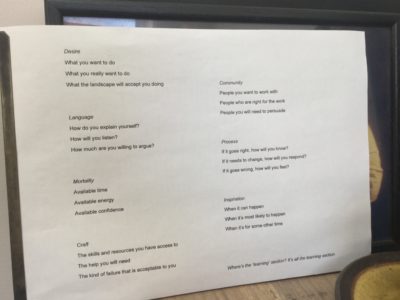

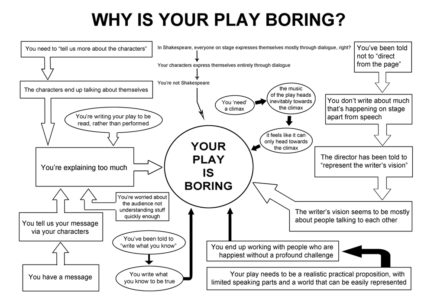

The office is full of charts and diagrams and lists and reminders, that have begun to feel like the familiar voices of colleagues. Here’s some of them:

For most of today I’m working on a play called Babel’s Cupid. It’s about sex and translation. An epic love story.

A lot of the dialogue is presented as an act of interpretation between two people who share no common tongue, but on stage everything’s heard in a single language. So here, A is interpreting between B and C:

It takes some focus. The writing seems to be arriving in compact bursts of what Tanuja identifies, purely from its sound, as ‘happy typing,’ surrounded by 20-minute periods of wandering and staring out of the windows. I’ve decided to embrace it. I need the dialogue to feel instinctive, immediate, sometimes tangential – with an idea like this, it could get over-clever, thematic, fast. People could end up constantly saying what they mean, which would make for a bad old soup.

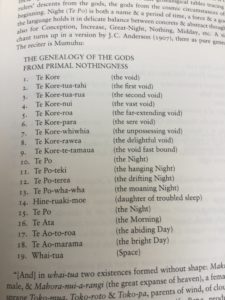

There’s only one book by my side when writing Babel’s Cupid, it’s called Technicians Of The Sacred: a luminous collection of poetries from around the world.

It’s not on the desk because of its subjects per se, but because of the way that the translations make me think differently about language. This list, from what is now New Zealand, is beguiling and weirdly comforting to me right now:

I run a company called Sleepdogs with Tanuja. At 2pm we have an online meeting with a motion-capture studio we’re going to be doing some experiments with (whenever there’s next the chance…) Everyone taking part in the meeting is in isolation. We’re all going to be seeing a lot more of the inside of everyone else’s homes, aren’t we?

After that I throw myself onto a torture device downstairs. For years I’ve relied on not being able to drive, and therefore walking everywhere, as my sole regular exercise. No more. As I sweat I listen to a podcast about the film Knives Out.

Rhian Johnson talks about developing the script, and how, consistently, everyone felt the first 20 or so pages were really rough, full of too much back-and-forth, but he had to hold his nerve – convinced that just because it was hard to read didn’t mean it wouldn’t make perfect sense on screen.

Sure, I love stories about writers holding their nerve and ultimately being right, who doesn’t? But then I also spent some of the weekend watching a documentary about a film project that went horribly, spectacularly awry, so I feel fairly balanced now.

The final bit of work today is to re-listen to some songs I’m arranging for a Sleepdogs musical we’re working on.

When arranging music I spend more time on it than any other type of work, my capacity for tinkering expands to ludicrous proportions. I’ve resolved to actively ration it during the isolation.

A phrase of Vince Gilligan’s keeps running through my head, about the dangers of too long a development period on any one thing: “Enough time to get it really, really wrong.”

I listen to a couple of tracks mixed last week, note down my immediate impressions, and switch off the equipment. Working day’s done.

So I’m not trying to ‘achieve’ any more in these times. Strikes me that the rush to unthinking product is part of what made the world’s response to the virus so inadequate. Why feed that mistake?

Although I am of course thinking of everyone who’s been ripped away, as I have, from projects and stories they deeply love, forced to put them on ice.

A couple of days ago a friend and fellow playwright, Adam Peck, asked online how theatre workers could keep themselves feeling relevant and useful. It’s taken me a while to frame my answer, but my honest feeling is: we’ve already done the work. For humans to feel better prepared to meet the strange – that’s always a huge part of telling stories.

There’s so many different kinds of grief people will be dealing with right now. And Adam, for instance, was lead writer on the recent stage adaptation of A Monster Calls – I’ve no doubt it will have strengthened plenty of people against current woes, in many different ways, tangibly or subtly, socially or subconsciously.

As for what comes next: I feel lucky, I’ve always been a writer who feels comfortable with uncertainties and unknowns, it’s part of my identity.

But don’t we all write for audiences ‘in the future’, by default, haven’t we always done that? That future feels further away, for the time being. But it’s still there.